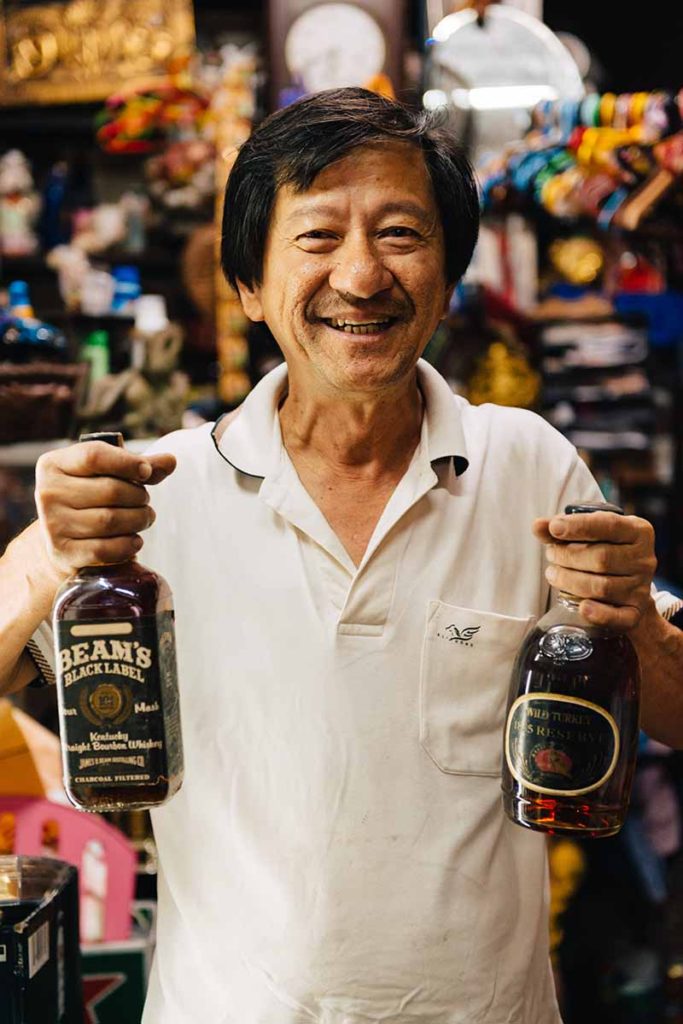

Dusty hunting at the Yeo Buan Heng Liquor Store in Singapore. By Dan Bignold.

For guardians of such a disorderly trove of alcoholic curiosities, David and Irene Yeo have decidedly straightforward tastes. Irene, David’s younger sister, says she likes Johnnie Walker Black Label. David, aged 58, prefers Martell Cordon Bleu. “Whisky burns too much,” he confides. Their business, the Yeo Buan Heng Liquor Store, has been open at 27 Chander Road in Singapore’s Little India for 50 years. Two out of a family of ten siblings, David and Irene took over from their father, who started the company 88 years ago. The business shifted several times before settling at this address, and when he took over, David also shifted the focus to alcohol. “My dad was selling household goods; I sell liquor. I’m a drinker. So I used the place to put liquor, to sell and display.”

David calls the stock “my collection”, one of the more subtle clues that Yeo Buan Heng is no ordinary bottle shop. Yes, there’s a steady stream of locals picking up cigarettes or bring-your-own beer to consume in the restaurants next door, but the unit is really a junk shop, with knick-knacks piled high and half the floor space impenetrable to all except mice and dust. But behind the glass counter – a counter filled, covered and surrounded by trinkets, boxes, obsolete electronics, chipped buddhas and abandoned toys – there is a vast wall of shelves packed precariously with spirits.

Some are new; some are more than 50 years old. Sifting through them takes an age, and lots of pointing. Irene carefully takes bottles off the shelf, re-arranges others, fingertips barely reaching one (inevitably behind) that’s caught my eye. With very few clear surfaces to rest anything on, it’s a delicate operation. You have to build up trust before Irene will let you go behind the counter yourself, and when you do, you’re navigating just as many bottles underfoot as there are on view. On my two visits so far, I have eventually winkled out (and in some cases bought) a 1970s Black Label, a 1980s Glen Elgin 12-year single malt, a 1960s Campari and a 1980s Old Charter bourbon. There are dozens more: blended scotch especially, motley liqueurs, and even some wine (best avoided – bottles at Yeo Buan Heng are neither air-conditioned nor horizontally racked).

In most cases the stock would have been entry-level when it first went on sale, but there are exceptions, such as some Walter Raleigh 25-year-old scotch and two bottles of limited edition Raffles Hotel Macallan. The passing of time has increased all its rarity, however, and this is the pleasure of what Americans call dusty hunting – turning up bottles from a bygone era, not necessarily expensive back then, but very hard to find right now. Identifying age clues, such as a tax stamp over the cap of the Old Charter, which dates it as pre-1985, when the USA stopped using such wrappers, is also part of the fun. A Laphroaig, on the other hand, disappoints, because it already carries the Royal Warrant of the Prince of Wales – awarded to the distillery in 1994. It’s a similar story with a promising, dust-caked Wild Turkey “1855 Reserve”: online investigation dates it modestly – circa 2002. More rewarding is a very old bottle of Camus – see panel. Most labels are damaged, and you shouldn’t expect original boxes, but if you check each bottle against too much evaporation, then what’s inside should be intact and therefore drinkable.

Questions of fakery and illegal trading do cross my mind. But there is something innocent about the whole Yeo Buan Heng set-up that answers doubts. If nefarious, wouldn’t the focus be on better-known brands, instead of all these forgotten scotch blends? Then there’s the price. David and Irene aren’t fools – they want good money for that Raffles Macallan, and they know the current value of Japanese whisky. But for the rest of it, they are way below auction websites. The 1980s Glen Elgin can be found online for 150GBP, albeit in perfect condition and with a box; they sold it to me (no box) for 110SGD. If dodgy, the whole operation, including prices, would be much more closely thought-through.

How these bottles ended up being on sale at an open- fronted Little India store in 2017 has little to do with the modern booze trade. Although David and Irene do still run some kind of wholesale operation, supplying neighbourhood nightclubs with new bottles, many of these dusties were bought overseas. “We used to get trading incentives by the companies – free air tickets,” he explains. “We go, we buy. We pay tax and ship.” In other instances, acquaintances sold or gifted him entire collections, “because maybe they now drink wine not spirits,” he suggests.

The truth, as the chaotic state of the shop proves, is that David and Irene are simply hoarders. You sense they have a complicated relationship with their stock; the bottles aren’t just commodities to buy and sell. David says he won’t deal with rude customers, only people who are “honest”, and then repeats three times “wenhua”, Mandarin for culture. “We want to see if people are really interested or not,” explains Irene. “Asia has no more this kind of liquor shop,” says David, and unlike Irene’s pronouncements on rum – “Bacardi Gold good for slimming, Myers Dark good for asthma, and Tanduay Gold Seal good for sex” – I think he’s probably right.

I pondered whether I should even write this piece. Prices might go up. Others will raid the bottles I am eyeing up for myself. Why not keep it quiet? I also checked with David whether he is ok with magazine exposure – worrying again about a liquor licence, tax and Irene repeatedly having to climb to fetch bottles from the top shelf. “I have my licence. If anyone dare to scold me, I can show them,” David declares. And then he offers to advertise DRiNK on the side of his van, in exchange for this article. I realise then that though he may be a hoarder, he’s still a businessman. Irene and he will appreciate the extra trade, especially from spirits enthusiasts. And anyway, Yeo Buan Heng desperately needs to free up some shelf space.

Hunting for clues

We dig into the origins of a few of Yeo Buan Heng’s old bottles

1. Beefeater London Dry gin

Clues as to the age of this Beefeater bottle began by matching it to a vintage Beefeater ad on Pinterest, from 1971. Emailing a photo to Desmond Payne, Beefeater’s master distiller, produced even better results. Payne noticed the Queen’s Award to Industry logo, marked 1966, on the front label. “We won this award in ’66, ’69, ’71, ’76, and ’85,” he explained. “I feel sure that Burroughs would have updated their labels to show the latest award – so it’s fairly safe to assume the bottle is somewhere between 1966 and 1969.”

2. Camus Hors D’Age cognac

The label is badly damaged here, but the neck sticker shows “Hors d’Age”. An email to Cyril Camus, current president of the house, confirms this as a 1960s precursor to the house’s modern XO blend. “As you know, cognac does not age in the bottle, so taste will be as it was then,” he added.

3. Schenley OFC 8-year-old Canadian whisky

This one was much easier, since Canadian spirits had tax stamps affixed over their caps until 1995. Although damaged, this still shows 1954 quite clearly – but note that these dates refer to the distillation year (not bottling) of the youngest spirit in the blend, identifying this as from 1962.

Yeo Buan Heng Liquor Store 27 Chander Road, Singapore. +65 9455 2035.

This story was first published in Issue 06 of DRiNK Magazine.