The introduction of the cauliflower to the European diet shaped the modern gin we know today. By Tom Egerton.

These days every bartender worth their salt is more than familiar with gin. The juniper-laced spirit has undergone a miraculous rebirth – from the dark days where you could count gins on one hand – to a global market force. Fantastic gins are being created all over the world, from macro producing juggernauts to micro produced wonders showcasing native botanicals and weird and wonderful inspired gins.

There are gins that have been shot to the edge of space, gins designed by artificial intelligence and gins created in custom collaboration for some of the best bars in the world. There’s been seminars, books, treatises and odes devoted to the spirit, awe-inspiring palaces to celebrate gin and many now know this spirit inside and out.

But what if there’s a part to this story that has been forgotten – a quirk of causality that evolved gin to become more than just a juniper-rich distilled spirit? What if there was a secret origin story – lines of history we’ve failed to connect? What if one single ingredient became part of a societal change that impacted entire industries, caused a financial crash and gave birth to the spirit we knew today?

That ingredient is cauliflower.

To understand how cauliflower led to the first modernised gins, we first need to understand the history of the spice trade. The Dutch Physician Franciscus Sylvius is widely thought to be the first to prescribe a distilled spirit flavoured with juniper to his patients in 1550. Juniper has been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years, showing up in the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs, imbibed with sour wine by the Greeks and used in medicinal practices by Navajo tribes of North America.

Juniper was thought to be an antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, treatment for tuberculosis and rheumatism, a source of calcium and even as a method of birth control. This medicinally valuable ingredient was not expensive, and the range of naturally growing juniper varieties spreads from the expanse of Siberia all the way to North America. The hardy bush grows wild and plentiful across most of the northern hemisphere.

On the other hand, spices were often worth more than their weight in gold, with taxes and goods often paid with spices due to cross-continental trade routes and no global unifying currency. A listing from a 12th Century price table lists the worth of a pound of nutmeg being worth as much as “seven fat oxen”.

First carried by horse or camel from the region of Southeast Asia, predominately the archipelago of Indonesia and lands of India, fragrant spice was traded along the lengthy and taxing Spice Route – around 15,000km overland. The price of undertaking this challenging journey was attached to each individual aromatic clove or piquant pepper.

Then as now people saw the cost of spices and equated expense with quality and so spices became a mark of immense wealth. What we know today as simple pantry ingredients such as cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg were associated with the hugely wealthy European royalty and upper classes in the Middle Ages.

Marijke van der Veen, emeritus professor of archeology at the University of Leicester and an expert on the historical importance of the spice trade says on the matter: “Spices give the elites an opportunity for extravagant display, and it emphasises to everybody else that it is out of reach.”

The Portuguese – who were desperate to break the Arab trader’s monopoly on the spice trade – established the first sea trade route when Vasco da Gama made landfall in Calicut, India in 1498. This sea route marked the beginning of European dominance in the spice trade and its riches and values. In the 17th Century, the Dutch East India Company (arguably one of the world’s first corporations) began to use private wealth and mercenary armies to conquer the Spice Islands – parts of Indonesia and Malaysia – in order to capitalise on the trade of spices to Europeans obsessed with the allure of these luxury commodities.

Market forces inevitably followed and the over-supply of these once rare commodities ensured that the price of spices began to tumble in European markets, while other commodities such as silk became much more financially viable to import from the East. Peppercorns suffered import fluctuations between 5300 and 2700 metric tonnes annually in European markets, while all the classical pantry spices began to find their values lowered. Cinnamon was an exception and retained its value due to the incredibly popular mix with liquid chocolate – which was newly imported from Central and South America – and was a particular favourite of the extravagant courts of Europe’s decadent monarchies.

To recap, as the 16th Century came to a close, spices went from a rare and almost mystical commodity from the exotic Far East to an extravagant luxury. They were enjoyed by the upper class of European society, typically found in the recipes of the Middle Ages and appearing in the heavy sauces and pies, as well as to preserve and sometimes disguise the aroma of spoiled foodstuffs.

Enter the cauliflower.

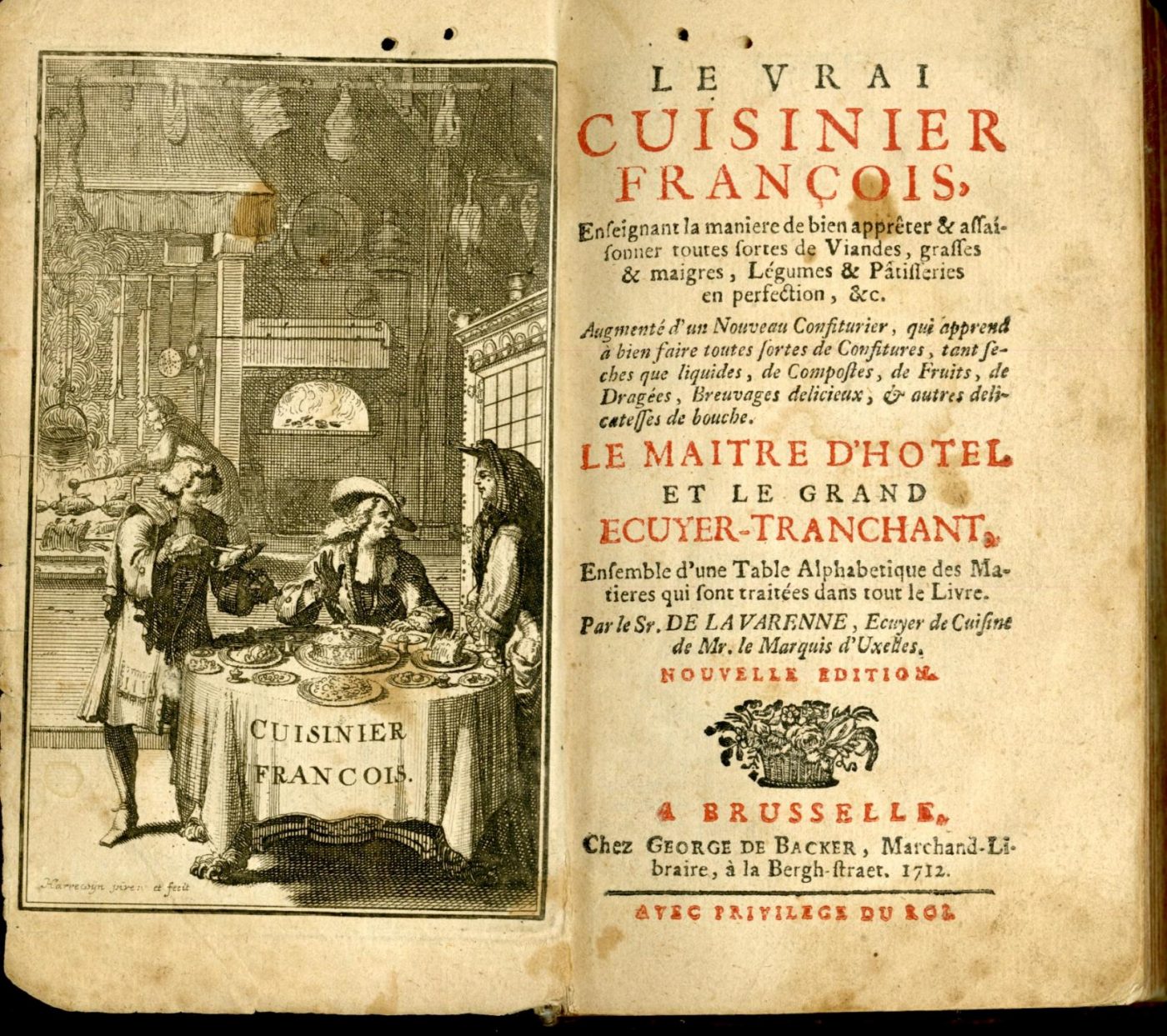

In 1651, the culinary world saw a revolution which changed how all of Europe would dine. François Pierre La Varenne published Le Cuisinier François, a seminal work which formed the modern basis of French cooking. The early forms of master sauces were first recorded including a proto-hollandaise sauce and bechamel recipe, the first usage of egg white for clarification and the introduction of new vegetables to the European diet – including a relatively new vegetable to Continental palates: the cauliflower.

The most important shift caused by Varenne’s work was that the heavy sauces and spice-rich recipes inherited from the Middle Ages were replaced with locally grown herbs and a focus on fresh local produce. This was a revolution for European cuisine and it spread rapidly to the courts and kitchens across Western and Central Europe. The book found its first English translation in 1653 and was subsequently translated to all major European languages as demand for the new modern French cuisine grew.

In London the demand for gin was stronger than ever during this time, with the soldiery of England bringing back a taste for juniper spirits back from the mercenary wars of William of Orange in the low countries of the modern Netherlands.

Taking the throne in 1702, Queen Anne inadvertently created a booming market for cheap home-made gin after she canceled the charter to the Worshipful Company of Distillers, which essentially opened up the market to anyone who had distillation apparatus and access to surplus grain (or neutral spirit) which would form the base of the juniper spirit of the day.

The 1700s saw a tumultuous time in the history of gin including the famed “gin craze” which was spearheaded by a semi-teetotal organisation dedicated to minimising the social impact of cheap gin while extolling the virtues of ‘good and proper’ British Ale. After all, this was an era where water was less trustworthy for inner-city dwellers than drinking alcohol, where replacing water with ale had long supplied a working-class solution to the issue of tainted water. However, when gin became even cheaper to procure than ale there was a shift towards the abuse of the spirit by the large underclass of underemployed and socially traumatised early Industrial Age Londoners who had nothing better to do than to drink rot-gut gin to pass the time.

This moral panic peaked in 1751 with the publication of William Hogarth’s “Gin Lane”, an etching which purported to show all the social harms which were caused by the cheap spirit.

As a result of the gin craze a series of Gin Acts were codified during the 1700s which sought to control the distillation, taxation and sale of gin, but these legislations took years to see a wider effect in society. The raising of taxation and material cost would eventually drive the majority of cheap gin producers out of business, and due to the ballooning operational costs gin was forced to remake its image as a higher quality of spirit more in line with the image of the British Empire in the Victorian age.

1825 saw a slashing of spirits duties which led to higher production of gin and the changing fortunes of the now established wealthy gin merchants. This led them to invest in up-market modern public houses dedicated to gin with gas lights, stained glass windows and brass fittings which became known as ‘Gin Palaces’ and defined the archetypal English pub we still see today.

1828 marked the emergence of the earliest “Gin Palace”, which was based on the upmarket providores of the age, which focused on a wealthy sector of consumers. It is no coincidence that storied grand department stores such as Harrods (1834) and Harvey Nichols (1831) were founded in a similar mold to these opulent contemporary gin palaces, signifying their place in the new economic and social strata of the industrial age through their luxurious fittings and appointments. By the 1850s, there was estimated to be around 5000 palaces in London, with Charles Dickens referring to them in his writings as being “perfectly dazzling when contrasted with the darkness and dirt we have just left.”

So as the spirit gentrifies to something a lot closer to the dry gin we know today, how does the cauliflower come into play? Here we leave established fact and pose a more conjectural interpretation of a timeline, so until there is more evidence to back up my claims maybe don’t cite me just yet.

In the 1800s, England was still enjoying the bounty of the newly conquered so-called new world, importing exotic citrus fruit to London from the colonies they shared with Spain and France. Meanwhile, the value of spices from across the broad Asian theatre had been decimated by oversupply due to the diversification of supply chains created by the various East India companies. This newly realised globalisation of trade rendered ingredients once thought of as a luxury only fit for royalty or religious ceremonies to an accessible commodity.

The new elevated image of gin was met with the early 1900s Imperial mindset, when ruled the waves as Britannia around the globe and was master of colony, warfare and trade. We could propose that the introduction of a wider botanical ingredient bill to gins which occurred around this age were representative of the new world (citrus), the far East colonies (nutmeg, cassia, grains of paradise) and traditional European ingredients tied to medicinal folklore (juniper, angelica) creating a spirit representative of the British ideal of naval dominion over the world and their commercial colonies. Gin embodied the riches of the empire, with its pride and character defined by the British imperial system and the spread of their global commercial empire.

Without the introduction of fresh ingredients – including the humble cauliflower – into the European diet by Varenne’s work, the heavy and spice-laden sauces of the Middle Ages would likely have remained and the value of spice would not have plummeted. The prevalence of Le Cuisinier François throughout the courts and wealthy households of Europe led to a generational shift in diet and ingredients, creating a lasting culinary impact which we still feel even today.

Instead, the collapse of commodity value set the stage for the macro-producers who protected the spirit of gin during the dark ages of disco and sour mix

Without this cultural watershed leading to the lowering of value of spices of Asia these ingredients would have been out of reach to the post-gin act distillers which defined the earliest London gins. Instead, the collapse of commodity value set the stage for the macro-producers who protected the spirit of gin during the dark ages of disco and sour mix.

Simply proclaiming that cauliflower directly led to the invention of gin is somewhat reductive, and admittedly the headline was designed mostly to grab your attention. This article should serve as a means to inspire thought about the economic and social forces that led to the creation of the modern spirits we know and love today, looking beyond the marketing spin of why a spirit tastes the way it does and towards the very real stories of the historical factors which shaped these spirits, and in some ways how the spirits shaped the course of world history.

Alcohol has had an immeasurable impact on the human race and its development. Some of the earliest professional sexism can be traced back to the female brewers of beer during the Babylonian period, a position which held strong religious significance and which led to the contemporary archetype of the “witch” – huddled over a bubbling (actively fermenting) cauldron and wearing the traditional conical hat of the brewer.

Corn whiskey led to the creation of the United States; the British taste for over-sweet table wine led to the birth of champagne and Napoleon’s naval blockade led to the creation of not one but two completely unique styles of rum.

It’s often easy to overlook the real history of spirits and cocktails in a world full of marketing spin and carefully designed brand heritage, however it sometimes pays to cut through the noise and focus on the simple and minor factors which shaped the spirits we love today. Simple factors like the cauliflower.