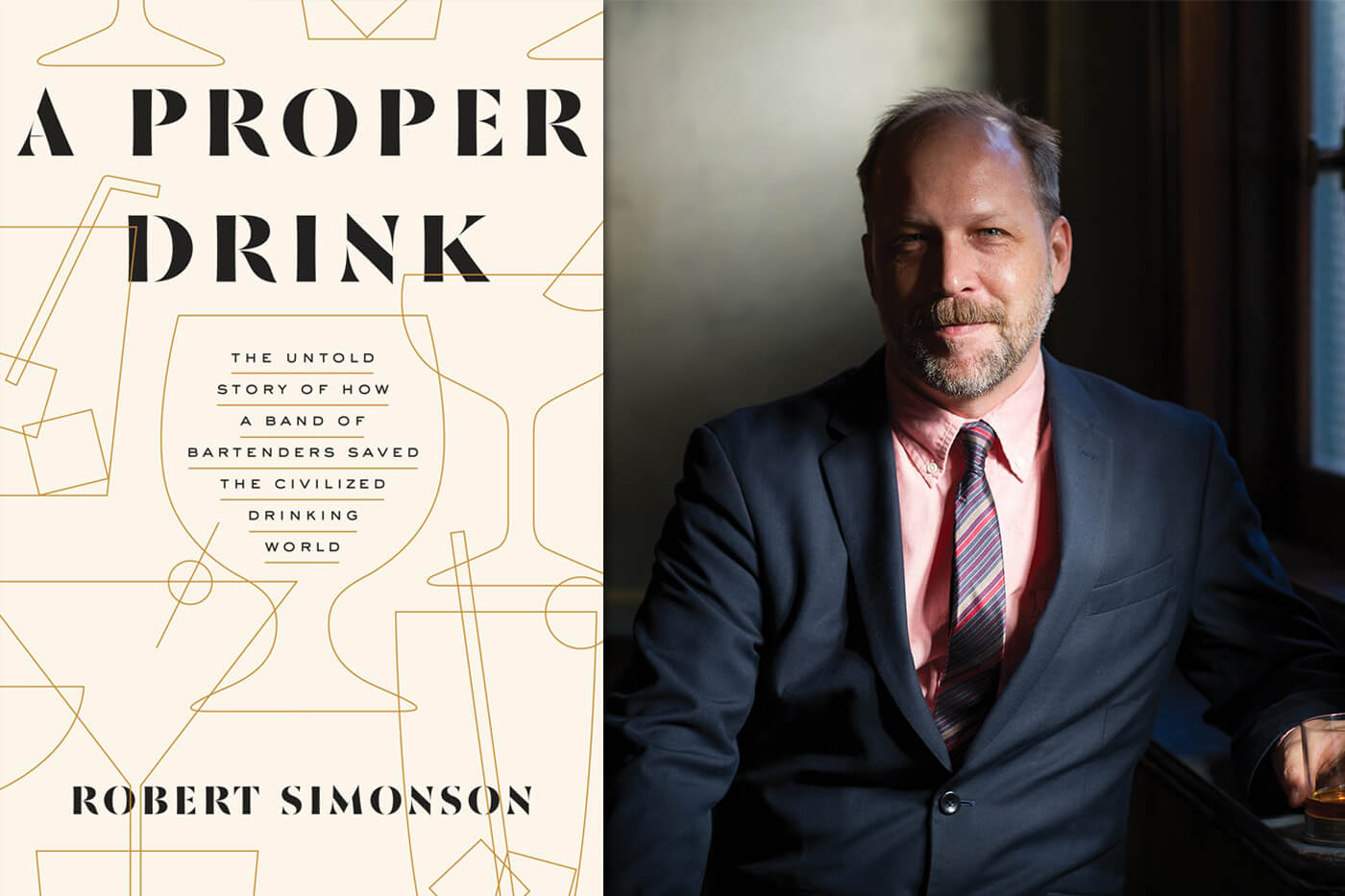

Robert Simonson’s superb chronicle of the great cocktail comeback should be a set text for anyone, anywhere, calling themselves a bartender, reckons Alexander Barlow.

Sure, Sasha Petraske might have been one of the most influential bartenders of his generation. But he was also, it turns out, a bit of a shit. That’s according to his friend Robert Simonson, a drinks journalist whose brilliant new book – A Proper Drink – anyone, anywhere calling themselves a bartender should feel duty-bound to read.

Petraske never really wanted to be a bartender, either; not to begin with, anyway. Born in New York in 1973, Petraske’s family were communists. Disrespectful of authority, as a youngster, he was a smart but delinquent drop-out. After a failed attempt to make it in California, he joined the army, hated it, and got kicked out after he told them he was gay (he wasn’t).

Back in New York in the late 1990s, he poured wine at a bar called Von – his first job as a bartender where began an obsession with correct barroom protocol that would later form the bedrock of his own netherworld. Set in a tiny space in New York’s Lower East Side (a former mahjong parlour, in fact), Milk & Honey was the world’s first modern speakeasy – a concept anchored in bygone cocktail classicism and its owner’s own rigidly ritualised rulebook of proper drinking politesse. No hats, no vodka, no dickheads: Petraske out-prissied everyone. And was loved for it. The speakeasy became the most widely copied genre in bar history and, in spite of his anal anachronisms and loathing of press attention, Petraske became a revered, if unlikely, cocktail kingpin.

“Milk & Honey was the first bar I knew that ran itself as if it was a rock and roll band” – David Wondrich

More bars would follow; none would make him rich: in 2015, he died from a heart attack, aged 42, in debt. Even so, Milk & Honey’s legacy lives on: an early salvo in the battle to restore order and art to the global cocktail continuum, Petraske its protagonist; the broke, tragic anti-hero of the whole thing. “If not for Sasha Petraske, we’d all be shaking Manhattans,” tweeted New York bartender, Matt Piacentini, after his death. “Except many of us wouldn’t be bartenders, and most of our bars wouldn’t exist.”

Exaggeration? Simonson doesn’t think so. Still, he’s by no means the only player in Simonson’s cast of cocktail conspirators. Like Petraske, Dick Bradsell, the awkward, sloppy grandee of the London cocktail movement, was another unlikely agitator who didn’t fit the mould of classic bartender. Still, as the inventor of more modern classics than anyone else in London (including the Espresso Martini and The Bramble) his influence was huge.

At the same time, on the other side of the Atlantic, Dale DeGroff played forefather to New York’s bartending revolution. In 1987, Rainbow Room, his seminal bar dedicated to then- forgotten classics, opened at the time when tools were scarce and proper maraschino just didn’t exist. Still, DeGroff’s principled service standards would inspire a new generation of bartenders that would go on to dominate the cocktail insurgency of the early 2000s: Julie Reiner, who opened Flatiron Lounge (“a breeding ground of expert bartenders that fed many of the subsequent New York cocktail bars”); Audrey Saunders, the Gin Gin Mule-inventing founder of Pegu Club; and, yes, Sasha Petraske. This trio, in turn, would inspire another wave of openings: Death & Co and Employees Only, among them. And so it continued, from San Francisco to Singapore, until the revolution was won.

Still, not all the architects of the modern cocktail kingdom were bartenders. Simonson happily shares the credit with a subset of evangelists: the upshot of David Wondrich’s scholarship is given colour and context; Tales founder Ann Tuennerman gets more than a passing mention; so does cocktail super-geek Robert Hess, both for his 1998 chat-site Drinkboy (“an agora for the future leaders of the cocktail renaissance”) and for being one of only a few non-bartenders to create a modern classic (The Trident).

“No other food or drink revolution has as tangled a relationship between the corporate and the craft as the cocktail movement

The labours of one former UK wine-seller are also well documented. “The most important person in the industry in the last 15 years isn’t Dale DeGroff; it isn’t Audrey Saunders; it’s Simon Ford,” says bartender Eben Klemm. “He’s done more to create the international community than anyone else.” How? Ford was the industry’s first brand ambassador – a position invented by happy accident when a tiny UK distillery asked him to rep its gin in New York by door-knocking the city’s best bars. (Long before craft brands, it was, reckons Simonson, “a suicide mission”, one that often brought Ford to tears).

Still, his eventual success would change the industry forever: not only did he send Plymouth Gin’s sales into the stratosphere, Ford provided a blueprint for liquor brands to infiltrate the movement. The bartender-buddying, salesman-as-educator cover would be widely copied: armed with bottomless expense accounts, the industry’s brightest talent swapped the bar for gilded ambassadorships, glad-handing bar staff around the world, allowing ideas to pollinate between cities at an unprecedented rate. Suddenly, a local movement had gone global; a one-time placeholder job now had prestige and prospects as a new era of “bartenders with business cards” had arrived. Along with the conventions and competitions that would follow, the craft had been co-opted; Big Booze had found its in; mixology meant money.

At what cost? In an industry with few dissenting voices, Simonson probably deserves credit even for asking. His answer is even-handed. “No other food or drink revolution has as tangled a relationship between the corporate and the craft as the cocktail movement,” he writes. On one side, the drinking renaissance could not have happened with the support of big brands. On the other, bartenders now expect fame as a given and a new generation of brand-backed “uber-cocktail bar” pursues profile and prizes to the point where the drinks, the guests, become secondary.

So where do we go from here? In one of the book’s only disappointments, Simonson doesn’t say. Still, it’s clear he’s nostalgic for simpler times: an era when simply switching out sugar for honey syrup was a small revolution; those hard- headed days when bartenders fought to revitalise their profession and convince the world of their art. Unsparing and unsentimental, Simonson knows they didn’t always get it right: Sasha Petraske made his Sazerac incorrectly for an entire year before anyone noticed, while cupholder-crank Phil Ward can remember exchanges with his drinkers that suggests that rep for bartender-as- self-serious-asshole was not entirely undeserved. “People would come in and say, ‘I’d like a Cosmopolitan’. And I’d say, ‘You don’t want a Cosmopolitan. There are so many better things to drink.’ I was out of my mind. I was fighting with people.”

Other bartenders remember similar haughtiness. “I cringe at some of things I did back then,” says Toby Maloney. “Like not making a Vodka Martini because I thought it was beneath me.” Still, the militant seriousness was necessary; without it, the revolution would not have held up, reckons David Wondrich, whose observation of Milk & Honey would one day be apt for an entire movement of brusque, no-bullshit bar pros: “It was the first bar I knew that ran itself as if it was a rock and roll band. With the owner and the bartenders having this strong camaraderie, like it’s us against the world,” he says. “[Bartending] wasn’t just a job, it was a cause.”

A Proper Drink by Robert Simonson is published by Ten Speed Press.

This story was first published on Issue 04 of DRiNK Magazine’s Greater Asia edition. Order a subscription here.