Medication turned into relaxation, the distinguished ritual of the aperitif has given birth to an extended family of drinks – and a far more civilised world, says Adam Devermann.

Prior to dinner, outside bars scattered across Europe and the Mediterranean, tables are being cast slowly into the shade of ancient columns and surrounded by the muffled clatter of a kitchen alive with its first rush of the day. On these grand piazzas, open to the departing sun and the chatter of passing pedestrians, and on the terraces of cafés tucked down meandering tree-lined lanes, a deeply entrenched evening ritual begins.

The Italians call it aperitivo, the French an aperitif. Predominantly a European phenomenon, the word aperitif may mean many things: a period of time (roughly between 6 and 9pm), or a social activity, and even a style of drink. Most important to bartenders is the latter – a style of drink which in its simplest form can be defined as spirits or wine to be taken prior to a meal to awaken the palate, and then the stomach (the word’s root means to open, or uncover).

An aperitif is akin to a liquid hors d’oeuvre. Though the science is disputed, many are firm believers that a light aperitif can actually alert digestive enzymes to the forthcoming meal. But the difficulty lies in what qualifies as an aperitif. The traditional aperitif spirits are often low in alcohol content, flavoured with herbs and plants, possibly bitter, always refreshing; but an aperitif may also be aromatised or fortified wines, or perhaps something simply effervescent, such as a sparkling wine. Such definitions hardly provide a sturdy framework, however, and should only be used as a starting point.

History and tradition

Like all things worthwhile in history, the traditions of the aperitif are masked in misinformation and mystery. Some claim that in 1786 Antonio Benedetto Carpano, a lover of moscato wine and a shop assistant in a liquor store beneath the portico in Turin’s central Piazza Castello, created an aromatic wine using herbs and spices. Today, many recognise his creation as the birth of vermouth.

While we have Carpano to thank for vermouth, vermouth is not the only historical foundation for the school of aperitifs. Ever since the beginnings of distillation, humans have been fascinated by the nourishing and restorative properties locked inside spices, flowers, herbs, fruit, barks, roots, and other aromatic plants. Ancient civilisations such as the Romans, Chinese, and Egyptians all had versions of flavoured alcohols, though it’s unlikely these would have been similar to modern apéritif. Closer would have been the recipes of Arnold de Vila Nova, a 13th century Spanish alchemist who wrote a book, called The Boke of Wine, dedicated to the subject of distilling wine and then flavouring the distillate with herbs and spices. In these early years distilled spirits were consumed daily due to their comparative safety to water. The subsequent flavoured versions were considered restorative, curing, even magical. Alcohol’s ability to extract and preserve the essence from botanicals was even thought by some to be a divine gift.

When one speaks about divinity, the Church and religion are never far behind. In the Middle Ages monks were adept at distillation, and for more than 200 years, beginning roughly in the 1400s, monastic orders lead the way in developing recipes and theories on the curative properties of flavoured herbal distillates. Looking at a back bar today, you can still see clear evidence of the monks’ influence on the world of aperitifs.

As the popularity of these cure-all spirits increased, so did their commercial value. Outside the monasteries, more and more royally (and self-) appointed alchemists began experimenting with vegetal combinations, providing a steady flow of liquid remedies for the public. Many were also producing digestifs – spirits to be taken after a meal to aid digestion. These often shared the same ingredients as aperitifs, and are still touted by some as medical tonics – such as the German digestif Underberg, or the infamously bitter Fernet Branca from Italy.

Dates to know

There are numerous other historical examples across Europe of the proliferation in aperitifs and digestifs.

1575Lucas Bols began his distillery in Holland (which eventually became the current global giant, Bols) by producing bitters and kummel, a caraway and cumin liqueur.

1775The most famous female distiller in history, Marie Brizard created one of the first commercial anisettes.

1846Parisian chemist Joseph Dubonnet introduced a wine-based aperitif for the malaria-plagued French soldiers in North Africa. His recipe took the bitter edge off the commonly used ingredient quinine, known to help fight malaria, by fortifying wine with grape brandy while simultaneously adding flavourings such as chamomile, coffee beans and orange peel.

1860Gaspare Campari invented his still secret recipe for Rosa Campari, and began commercially producing the now ubiquitous bitter-sweet red liquor.

1872The birth of another popular aromatised wine created by Paul and Raymond Lillet.

1885Emile Giffard created his mint-flavoured Menthe Pastille in France. By this time, the commercial value of aperitifs and digestifs had been fully realised, and they were being drunk as much for pleasure as for their medicinal value.

Cocktails

And yet for all of the recorded history of individual spirits or drinks eternally linked to the word aperitif, there is little exact evidence of how the tradition began. Neither an exact date, nor a written procedure, nor an inventor of the term seems to have been recorded. Never mind. The aperitif was already safely embedded not just in European countries but globally, thanks to continued re-invention. Sometime after the mid-19th century aperitif-style products had been adopted by American cocktail maestros; vermouths were used in a world-famous drinks like the Dry Martini and the Manhattan, and other liqueurs such as Cointreau and Maraschino found their way into the canon of classic cocktails. Indeed by the end of the 20th century, Europe was drinking far fewer of these products by themselves, and taking them in cocktails and simple mixed drinks instead. Not to say the aperitif ritual had died out, far from it; just that new styles of mixed drinks, cocktails included, had been substituted in.

And the trend evolves. Now in Italy, for example, the Spritz – a blend of wine with a bitter aperitif like Aperol or Campari – is everywhere. But its purpose as an aperitif remains as close to its precursors as ever: a pre-dinner rite that bids farewell to the weakening sunlight and eases one’s mind away from the stresses of the day, and into leisure, comfort, friendship and festivity.

So, what is an aperitif?

As we have seen, the word aperitif does not explain a defined category of spirit or other alcoholic beverage. Rather it’s a type of drink, or ritual, and is by no means limited to just herbaceous liqueurs. Sparkling wines, champagne, or light bodied wines are common from France to the US, and are one of the most commonly sipped pre-dinner beverages. Adding a little crème de cassis to champagne to make a Kir Royale will also suffice for many. Spain’s famous dry sherry, served chilled, is a fine compliment to the traditional Spanish tapas.

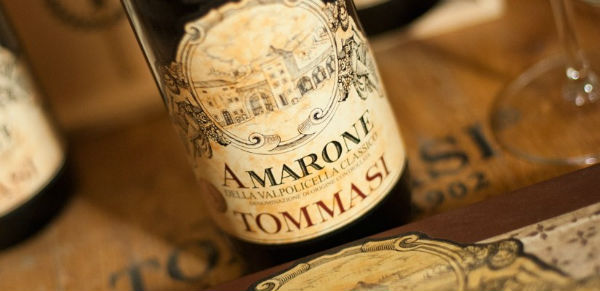

But Italy in particular may be able to boast the highest number of what can specifically be called aperitif spirits of any country. Each and every town still seems to maintain their own historic “amari”, or bitters, which are usually secret recipes of herbs and plants used to flavour a base alcohol. But how is the flavouring achieved?

The techniques for flavouring spirits have remained relatively unchanged since the days of monk-operated distilleries. There are four methods (which are not limited to aperitif or other liqueurs – think gin): compounding, infusion, percolation, and maceration.

Compounding. Method by which concentrated flavourings are mixed with a liqueur made of a sugar solution, added directly to a base alcohol. The most economical and uncomplicated way to produce a flavoured liqueur.

Infusion. Takes place prior to distillation, with the pre-determined flavourings steeped in a liquid. Widespread when using dry ingredients such as leaves or plants (think making a pot of tea), and is related to maceration.

Percolation. A distillate is placed at the bottom of a container, then heated and sprayed above flavourings contained in a net or screen, and then allowed to drip back down. As the heated distillate returns to the bottom of the container through the screen, it captures the intense aromas and flavourings (think brewing coffee). The process may be repeated multiple times. Vanilla beans and cocoa pods are common ingredients that require this method.

Maceration. Ingredients are steeped for a lengthy period of time, often weeks, in a distilled spirit to extract the desired flavourings and aromas. This method is often used for tender fruits, such as peaches, bananas, or berries.