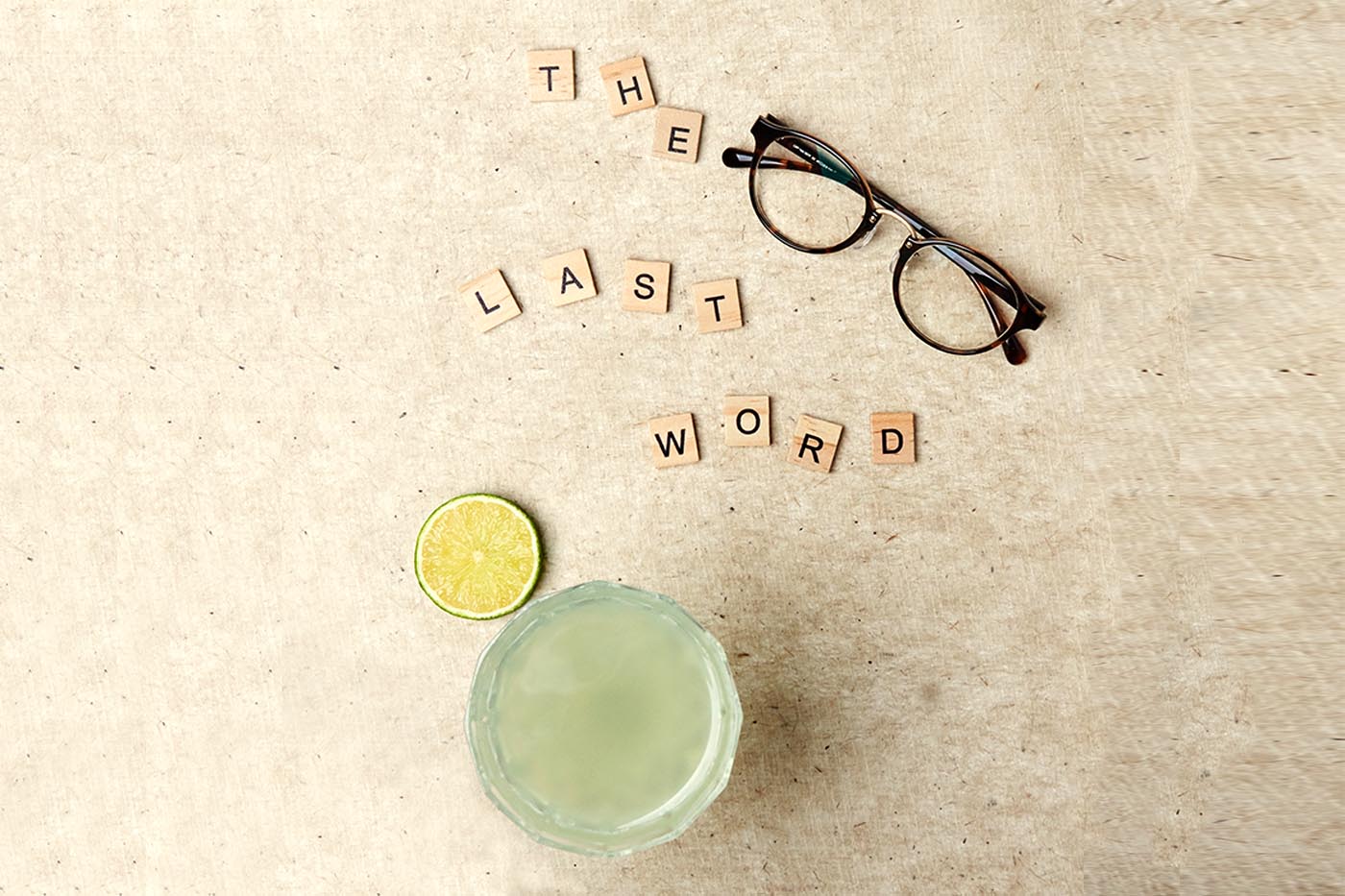

In the beginning was the Word… and the Word was equal parts gin, maraschino, Chartreuse and lime juice. By Seamus Harris.

A cult classic of the cocktail renaissance, the Last Word looks bizarre on paper. Equal parts bold juniper, sticky cherry funk, a Carthusian herb garden fossilised in honey and piquant citrus – the blending of two liqueurs plus an army of botanicals suggests saccharine anarchy. Early 20th-century cocktail books are littered with equal parts recipes that need tweaking, or emergency department heroics, to be palatable. But the Last Word is that rare prototype whose blueprint needs no revision. Once in the glass, the Chartreuse blends seamlessly with the gin and maraschino, while the lime turns cloying medicinal candy into richly perfumed lemonade. The key to the alchemy lies in the unlikely marriage of Chartreuse and maraschino. Two bold liqueurs, each used to hogging the limelight, upon meeting the pair somehow agree to share centre stage. Test this by swapping out the gin for another spirit. It is impossible to go too far wrong, and every variation will lead you on a different journey around the same labyrinthine flavour maze.

The Last Word originated in pre-Prohibition Detroit. Best known in recent years for urban decay, demographic collapse, deindustrialisation and municipal bankruptcy, in the early 20th century Detroit was the model of American modernity. Testament to this former greatness is the lavish neo-Renaissance clubhouse of the Detroit Athletic Club, still standing in the heart of the entertainment district opposite the landmark art deco Wilson Theatre. Fittingly, the DAC just happens to be where the Last Word first popped up back in 1916. The cocktail appears on old DAC menus and was clearly a house speciality, but despite its modern fame, the identity of its creator remains a mystery. Indeed, the Last Word was virtually unknown in its day, while no surviving recipe collections from the early 20th century mention it.

A mistimed birth seems at fault, with the Last Word taking its first faltering steps just in time to be knocked over by Prohibition. The recipe would have been lost forever but for a reference in Ted Saucier’s Bottoms Up (1951), and even that lone mention might have mattered little without Seattle bartender Murray Stenson’s passion for exploring classic drinks. Stenson is the hero we must thank for salvaging the Last Word from the ocean of anonymity, gently resuscitating it, and setting it loose to charm drinkers. Few other cocktails have inspired bartenders to such feats of creativity, and modern variations on the Last Word could fill a book.

The Last Word’s phoenix-like tale of resurrection is strikingly echoed in Detroit’s official motto: Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus (We hope for better things; It will arise from the ashes). Here is hoping that some of that spirit of rejuvenation spills over into beleaguered Motown itself. At least if numbers of new bar openings are any guide, it looks like Detroit may finally be back on the up.

Five dates to remember

1887

The Detroit Athletic Club is founded, initially as a modest establishment intended to encourage amateur athletics. In 1913, as Detroit rides the automotive boom, a consortium of local business leaders, determined to get themselves into shape and out of local pubs, finance the DAC’s transformation into a vigorous monument to their athletic resolve. By 1915 construction of the opulent clubhouse still used today is complete.

1916

A souvenir menu distributed to members of the DAC includes a Last Word cocktail. The cocktail was the most expensive on the menu, at a princely 35 cents – compared to a mere 15 cents for a Manhattan or Martini. Clearly, the DAC’s Last Word was something special, consistent with the use of exotica like Chartreuse. However, the lack of an actual recipe or any mention of ingredients means the recipe that survives today may differ from the DAC original.

1917

Detroit goes dry on May 1, 1917, after the state government prohibits the sale of alcohol. A leader in temperance activism, Michigan signed Prohibition into law a couple of years before the rest of the country. Naturally, smugglers immediately begin spiriting booze across the Detroit River from Canada. Bootlegging becomes Detroit’s second largest industry, and the so- called Detroit-Windsor Funnel allegedly handles three quarters of the illicit liquor that enters the United States during Prohibition. However, we must dispel romantic images of Detroiters riding out Prohibition on a diet of Last Word cocktails. The bootleggers specialized in cheap whisky, and it seems no one thought to manufacture “bathtub Chartreuse”.

1951

Decades after the Last Word’s invention, Ted Saucier’s Bottoms Up gives the only surviving recipe. Tagged “Courtesy, Detroit Athletic Club”, the formula is “1⁄4 dry gin, 1⁄4 maraschino, 1⁄4 chartreuse, 1⁄4 lime juice. Ice. Serve in a cocktail glass”. Saucier continues: “This cocktail was introduced around here about thirty years ago by Frank Fogarty, who was very well known in vaudeville. He was called the ‘Dublin Minstrel,’ and was a very fine monologue artist.” Fogarty performed in Motor City in 1914, 1915 and 1916, and the January 1917 edition of the DAC News (a monthly newsletter distributed to club members) reports on Fogarty giving a private performance at the club. While there is no evidence to support claims Fogarty invented the Last Word, he may well have taken it to New York – Saucier worked as the publicist for the city’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel, so his “around here” refers to the Big Apple.

2003-2004

Bartending legend Murray Stenson revives the Last Word while working at Seattle’s Zig Zag Cafe. With the cocktail renaissance gathering steam and pre-Prohibition boozing all the rage, the time is ripe for a complex herbal sour using two obscure liqueurs. Bartenders are soon riffing on the Last Word. I like the variations that stay nearest the original, such as by simply swapping gin for another spirit. The Closing Argument (creator unknown) introduces mezcal, while the Wordsmith (credit to Chuck Taggart of Gumbo Pages) hits the accelerator with a high-ABV Jamaican rum. More adventurous possibilities also exist, though as you hack through the jungle of variations the links to the original grow ever fainter. One of the more popular exotic variations is the Division Bell (from Phil Ward at Mayahuel, New York), which blends mezcal, Aperol, maraschino and lime. Then there are novelties like the Oh My Word (from Sother Teague at Amor y Amargo, New York), where old tom replaces London dry, and Amaro Montenegro and lime bitters stand in for lime juice – a result of the bar’s curious no citrus policy.

Recipe (Click to view)

The Last Word