Get to know the Victorian-style mulled wine concoction made famous by Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. By Elysia Bagley.

When it comes to authors and their affinity for boozy libations, Ernest Hemingway tends to get all the love. Being the season of giving, let’s not forget to give some thanks to another literary great who has no lack of spirit (forgive our pun) in his classics – Charles Dickens. The 19th-century British novelist was well known for his knowledge of spirits and drinks, a fact further elucidated by his great grandson Cedric Dickens in the 1980 book Drinking with Dickens. Yes, there’s a book all about Dickens and booze, and that’s something to celebrate.

The novelist and satirist doused his books with references to Victorian tipples, those both forgotten and living on today. That includes arguably the Christmas holiday’s most esteemed written work: A Christmas Carol. Published in 1843, this is the timeless tale of the original Grinch – the rich, greedy curmudgeon Ebenezer Scrooge – and his journey through time with the ghosts of Christmas past, present and future. That narrative subsequently leads to Scrooge’s self-realisation that he’s spent years being, well… a total dick to his city, his family and his undeservedly devoted employee Bob Cratchit; followed by a complete turnaround through which he becomes the embodiment of the Christmas spirit for the rest of his days.

A Christmas Carol is also home to one of Dickens’ more particularly well-cited placements of alcoholic potations within his novels. In the story’s final scene, Scrooge, feeling a surge of the Christmas spirit after his wild transformation, needs a holiday cheer-inflected drink, and so comes to the wretched abode of poor old Cratchit, who’s about to sit down to a meagre holiday meal with his family…

“A merry Christmas, Bob!” said Scrooge, with an earnestness that could not be mistaken, as he clapped him on the back. “A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you, for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob!”

Scrooge and Bob Cratchit enjoying a Smoking Bishop. Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol in Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, 1843 First Edition

So what’s a Smoking Bishop? In the simplest terms, it’s a holiday mulled wine with port. But there’s much more to it than that.

As shared by historian and wine master Elizabeth Gabay in an article on NPR’s The Salt, the Bishop is the most famous of a family of warm drinks – mainly punches – called “ecclesiastics”; concoctions with names which, in Victorian England, essentially stood as sippable versions of religious mockery. They were even sometimes served in bishop’s mitre-shaped vessels, explains Gabay, for another level of ridicule.

Dick Humelbergius Secundus (believed to be a pseudonym for English author William Beckford) alludes to this jest in his witty 1829 work Apician Morsels, or Tales of the Table, Kitchen, and Larder, referring to the drink as a popular “Oxford nightcap”: “It is not improbable that this celebrated drink… derived its name from the circumstance of ancient dignitaries of the church, when they honoured the university with a visit, being regaled with spiced wine.” Regaled indeed – in 19th century Protestant England, partaking in this aptly named drink would’ve been a cheeky dig at the Catholic church.

The Bishop is only one of many such “clerical drinks” made popular during the time. In Food and Cooking in Victorian England: A History, Andrea Broomfield identifies others such as Smoking Pope (burgundy based), Smoking Cardinal (champagne based), Smoking Archbishop (claret-based) and Smoking Beadle (ginger wine based). The port-based Bishop’s popularity and endurance through time is undoubtedly attributed to its place in A Christmas Carol.

Published in 1843, A Christmas Carol and Scrooge’s serving of the Smoking Bishop also acted as a commentary on the era’s class divides. Being a (formerly) underpaid bookkeeper with barely the means to feed his family, Bob would not have had the means to purchase port, even on such a special day as Christmas. Scrooge, on the other hand, as a money-lender, probably had a cellar full. “Working-class Victorians,” writes Broomfield, “could not afford such fancy drinks, but they often enjoyed a bottle of homemade wine with their Christmas dinner… The Cratchits, in Scrooge’s version of Christmas Present, treated themselves to a holiday hot gin punch,” the latter being a drink she specifies was popular among the poor at the time. Thus, Scrooge expresses his newfound charity by offering Bob a very special treat to show he’s turned a new, more generous leaf.

And there’s something else to be said about Scrooge and Bob sharing in a glass of punch, particularly – it implies togetherness in a way that a standalone glass of even Scrooge’s priciest port does not. The punch bowl is a communal drinking vessel; bringing people together for nothing other than merriment, and sharing such a holiday tipple is a British pastime that remains a quintessential symbol of Christmas togetherness today.

As for the recipe, one of the earliest versions can be found in Apician Morsels:

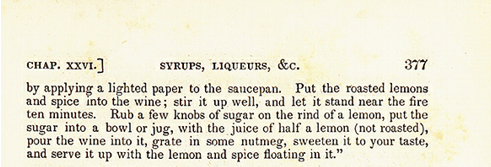

Make several incisions in the rind of a lemon; stick cloves in these incisions, and roast the said lemon by fire. Put small but equal quantities of cinnamon, mace, cloves, and allspice, and a race of ginger, into a saucepan, with half a pint of water; let it boil until it be reduced one half. Boil one bottle of port wine; burn a portion of the spirit out of it, by applying a lighted paper to the saucepan which contains it. Put the roasted lemons and spice into the wine; stir it up well, and let it stand near the fire ten minutes. Rub a few knobs of sugar on the rind of a lemon; put the sugar into a bowl or jug, with the juice of half a lemon (not roasted) pour the wine upon it, sweeten it to your taste, and serve it up with the lemon and spice floating in it. Ornages, although not used in bishop, at Oxford are…sometimes introduced into that beverage.

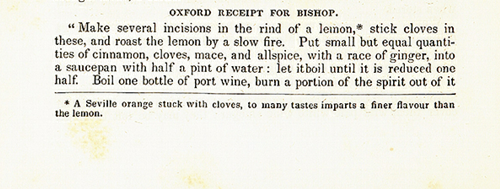

Not long after, a nearly identical version came with Eliza Acton’s 1845 recipe book, Modern Cookery In All Its Branches (see photo).

Smoking Bishop recipe; Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery, In All Its Branches: Reduced to a System of Easy Practice, for the Use of Private Families. In a Series of Practical Receipts, Which Have Been Strictly Tested, And are Given with the Most Minute exactness, 1845 American edition.

Today, the source of many modern riffs comes from Drinking with Dickens, which references its role in A Christmas Carol: “Bishop seems to have been a very popular drink, and no wonder,” Cedric Dickens wrote. “I discovered it many years ago and it quickly became a traditional winter party drink. Not only is its taste exquisite, but equally its medicinal qualities are great. You can feel it doing good. Temperatures go up, from the top of the head (bald heads turn red) right down to the toes.”

His recipe reads:

6 seville oranges

¼ lb sugar

1 bottle Portuguese red wine

1 bottle port

cloves

Bake the oranges in the oven until they are pale brown, and then put them into a warmed earthenware bowl with five cloves pricked into each. Add the sugar and pour in the wine – not the port. Cover and leave in a warm place for about a day. Squeeze the oranges into the wine and pour it through a sieve. Add the port and heat, but do not boil. Serve in warmed goblets and drink hot.

While the recipe originally called for lemons, over time they were universally replaced with the sweeter choice of oranges, with most sharing a specification for Seville oranges, aka bitter oranges. These, however, are a seasonal variety – Cedric Dickens notes them only being available in the winter months. Because of this, his text suggests making large quantities of the mix so that come summer, you can have a Bishop’s Cup. To do that, “don’t add the port, but fortify it with a tot of Orange Brandy. Before serving add the port and half pint of water.”

Lending a modern example of the drink’s seasonal versatility, The Dead Rabbit has summer and winter versions of a port-based punch in its drinks manual, which the bar calls the Archbishop – however, history decrees that an Archbishop was made with claret, as mentioned above.

Though they may’ve lost their anti-Catholic cheek and seem quite old fashioned, wine-based holiday punches don’t seem like they’ll die out anytime soon. Of course, mulled wines are a dime a dozen come winter, so this year, remember Dickens, and introduce your guests to a Bishop.

Recipe (Click to view)

Smoking Bishop