Mezcal, tequila’s more rustic hermano, is suddenly the cool kid in the sipping room. But with its surge, comes new regulations. Natasha Hong explains. Photos by mezcal.com.

With tequila firmly lodged in the global drinking consciousness and mezcal quickly growing in prominence, the last two-and-a-half years have seen the latter category rush to give itself regulatory coherence. The stakes are high: fail, and mezcal can give up hope of developing a proper knowledge base among its fledgling consumers, in the process becoming ever more likely to fall into the same quality trap that bedeviled tequila for decades. Succeed, and risk alienating aficionados and producers for whom a muddled status quo is better than a cleaned-up globalised future. Progress, so far, has been fraught, with attempts at re-coding Mexico’s myriad agave spirits greeted by a cacophony of impassioned (and often external) debate – some of it legitimate, some of it romanticizing. But with the noise around new legislation quietening down in the second half of this year, now could finally be mezcal’s turn to show the drinking world where agave is headed.

In late 2015, much of the conversation surrounding Mexico’s laws on potable alcohol centred around NOM-199, an initiative put forth by Mexico’s Secretariat of Economy, key players in the tequila camp, big spirits conglomerates, and mezcal’s Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM). NOMs, or the Norma Oficial Mexicana (Official Mexican Standard) are a collection of regulations governing all goods and services produced or generated within the country.

In 199’s case, covering Mexico’s alcohol industry, ire was raised among small producers and groups of vocal mezcal lovers outside the country – with closest neighbours the US leading the activism – when the new proposal sought to regulate the use of the words agave and maguey (a local word for agave) among outliers and producers that went against the rules of tequila’s and mezcal’s denominations of origin. These outsiders, the document recommended, would instead have to label their products with the broad Aztecan – and very obscure – term komil.

Groups like the Tequila Interchange Project charged that doing so would blur the distinctions between artisanally made agave liquor and the mixtos – blends of agave distillate with cane, corn or other grain spirit – churned out by big commercial brands. Fair point… so far. But while the fight for the palenques’ (mezcal distilleries) right to call their product by a more recognisable name raged in drinks-serious publications and online petitions, there was another more important revolution not getting its due attention – one that would conversely allow the genuine producers of agave-only mezcal, at the positive end of the komil spectrum, to earn recognition for their work: NOM-070.

Just like tequila’s NOM-006, the way for palenques to label their products mezcal is to comply with early NOM-070’s rules, which was first put to paper after consultation with 39 parties back in 1994 (they included a smattering of mezcal producers and, curiously, big conglomerates such as the Brown Forman Corporation, which didn’t itself have any mezcal in its portfolios). In those still-obscure days for the spirit, the framework was a loose set of checkboxes that sought to give the agave drink an identity – one that allowed up to 20 per cent of other carbohydrate distillate besides agave in its make up, which could be sold young or aged, among other requirements.

But with progress, comes change. In the 23 years since NOM-070 was first drafted, mezcal found new geeky advocates to the north of the border and elsewhere around the world. At last count, mezcal consumption outside the country matched the 1.4 million litres of liquid toasted down at weddings, births, funerals and why-nots inside Mexico. For a spirit that conducts a lot of its business in Spanish, off in mountains and along dirt roads in the countryside, what defined mezcal outside Mexico was mainly word of mouth – if you were lucky, from a passionate brand owner representing a stable of palenqueros (mezcal makers) under their label. The few brands savvy enough to consolidate and export mezcal have each done their bit to educate the trade. But without a document from an official, widely accessible source to acquaint drinkers on the hallmarks of the DO (denomination of origin), ambiguous brand names such as El Mezcalito – made with cane sugar and maguey – could potentially muddy the water for the mystified but eager consumer.

Enter the Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM) a not-for-profit, private organisation that works closely with the government to enforce the DO’s rules, and gets its money from the certification process it applies to liquids that want to label themselves mezcal. The executive committee, headed by chemist Hipocrates Nolasco Cancino, with Juan Jesus Lozoya Austin as secretary and mezcal brand Alipus’s Jaime Munoz-Castillo in the position of treasurer, put forth new reforms for the rules governing mezcal production in 2014.

After a series of eight public forums across the states in the appellation, with stakeholders airing their concerns and views on what would become the recognised framework for production, the CRM put forth their amendments to NOM-070 for government approval. As Sarah Bowen, Spirited Awards 2016 winner for her book Divided Spirits: Tequila, Mezcal, and the Politics of Production lauded in her comprehensive tome, “The process of debating the revised standard was by far the most democratic in the history of the regulation of tequila and mezcal.” Bowen also noted that, “On the whole, it reflected many of the arguments I had been hearing from small mezcaleros (mezcal producers), retailers, and mezcal activists for years.” After two years of work, an updated NOM-070-SCFI-2015 was given approval in July 2016, with 200 producers – small and large – and other stakeholders on board.

In the new document, nine states (Oaxaca, Guerrero, Durango, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Tamaulipas, Michoacan and Puebla) together form the world’s biggest denomination of origin, besting scotch whisky’s 78,000sqkm and tequila’s 110,000sqkm span with its huge 600,000sqkm. And it’s only going to grow. Cancino, at a talk sharing the word about the refreshed NOM-070 at Agave Love in Singapore in September, explained that with 24 of the 31 states known to be producing the spirit in the country, the appellation will continue to grow as long as local palenqueros, previously excluded, are willing to get organised to list historical evidence of their mezcal production, availability of native species of agave grown in-state, and the producers currently making the drink in the same state.

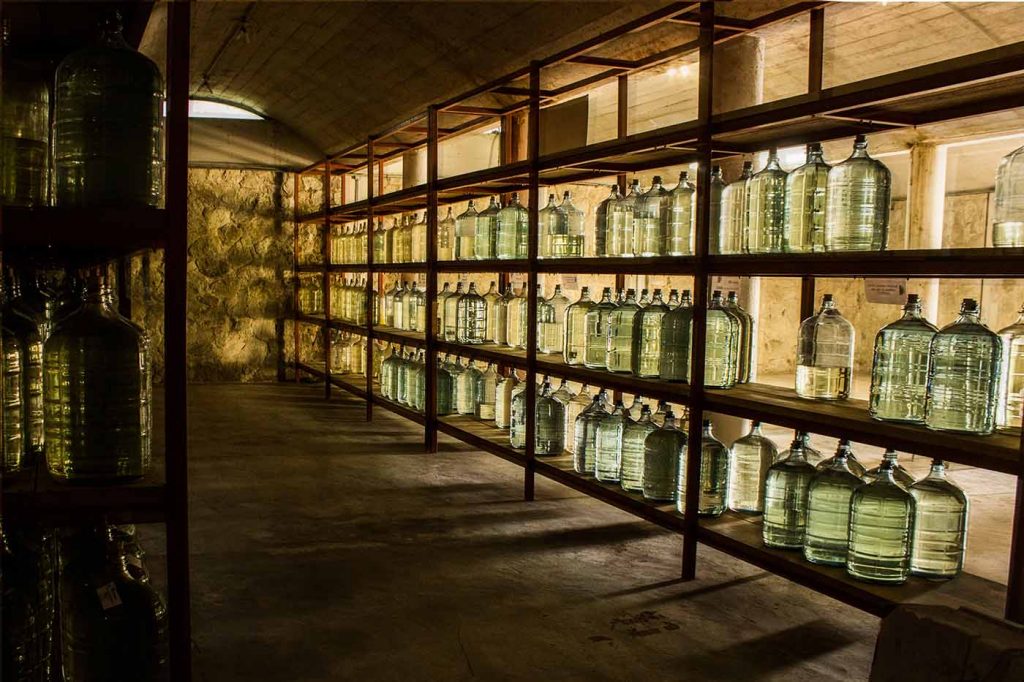

The new rules also require mezcal to be made 100 per cent with agave, and allow three production styles and six acceptable finishes for the sold spirit (see below for the full rules). As such, predictions for the next big thing in mezcal are beginning to buzz. Alipus’s Munoz-Castillo, at Agave Love, was putting his money on the madurado class of ancestral spirit. Soaked in cultural history, these mezcals are matured in glass bottles typically buried in earth in “mezcal cemeteries”. Each one is marked with a cross stating the date they go underground, as well as the date and special occasion they might be opened for (weddings, quinceaneras – coming of age parties for 15-year-old girls – or “economic crises”, joked Castillo). The result is a drink, he says, that is stabilised and pleasantly oxidised.

Industry aficionados, such as La Maison du Whisky Singapore’s bar manager and mezcal educator, Mauricio Allende, also predict that mezcal will go the way of whisky in the future, with plenty of speculation and hoarding of mezcals made with wild agave species. To ensure their sustainability, the 2016 edition of NOM-070 also requires that producers log the magueys they harvest at the community land registry, and replant two for every wild agave plant they dig up.

With the renewed energy surrounding the beverage, the CRM is also pushing a new initiative to broaden industry and consumer knowledge. While responsible brands like Del Maguey, Alipus and Real Minero have already taken the effort to list each bottle’s maguey species, producer and village of origin, all labels are now required to include that information, as well as earn a holographic badge from the CRM following lab tests and approvals of the batch. Consider it ahead of the appellation curve, then, that the CRM will be rolling out a QR code on its certification stickers to drive their message of quality, authenticity and traceability. When scanned, it leads the drinker to the new mezcal.com platform, which is working to painstakingly list every producer in every village in every state, complete with photos to help the end user understand and witness where and by whom their drink has been made.

Naturally, when a set of rules tries to hem in and hone down a definition of a spirit, fringe opposition is a given. Jay Schroeder, owner of Mezcaleria Las Flores in Chicago has expressed concern about the costs associated with certification. “By requiring small producers to pay for their own inspection, we’re burdening them in an economically untenable way,” he argues, and he may have a point. The CRM charges a fee for every step – from certifying the palenque, to rubber-stamping its labelling and lab testing its product – and this doesn’t include travel expenses for the verifier trekking out to the distillery.

The CRM, however, maintains that it’s working on getting government subsidies for the process, and that it isn’t profiteering. Its tiered pricing system that charges MXN0.40 (SGD0.03) per litre for small palenques producing 1,000 litres or less is said to make the cost feasible.

Allende, in helping with this article, also fretted about the complex technical language used in the document. “It’s not like I’m a Shakespeare of the Spanish language, but I’m educated and this is already difficult for me to read,” he explains. “To require someone who’s from a rural part of Oaxaca to understand this, pay the fees and go through all this bureaucracy might be unfair. I feel like it might facilitate a lot of charlatans to come and act as the middleman and take away the benefits for the small producers.” Questions also arise over enforcement. Despite the CRM’s commitment to respond to requests for verification in 15 days, it seems daunting for the CRM’s current team of 25 employees to journey out to every requesting mezcalero in what is now the world’s biggest appellation.

For states, however, that fall outside of mezcal’s currently approved zones, not falling in line with NOM-070 might give other producer groups the impetus to create their own DOs, to protect and elevate the heritage of their own spirits. Already, raicilla producers from Jalisco have formed a Consejo Mexicano Promotor de la Raicilla – still a promotion board, not yet regulatory – that is currently working on a denomination for Jalisco’s own strain of agave spirit, made exclusively with agaves angustifolia, rhodacantha, maximiliana and inaquiden.

In the meantime, the flurry raised around the controversial NOM-199 has gone quiet since the document’s public consultation period closed, with Cancino revealing at Agave Love that the new catch-all term has been changed from komil to aguardiente, a more widely recognised Spanish term – and therefore more palatable – for covering alcoholic beverages.

Ultimately, good legislation, when carefully considered, should bring advantages for those who fall under its purview. With mezcal’s increasingly elevated status around the world, secretary Juan Jesus Lozoya Austin notes how its growth is restoring pride to the category in Mexico: “When I started in the mezcal industry ten or 15 years ago, it was very difficult to see the sons of old producers working with them. But with new opportunities emerging, a lot of the sons who moved to the US to find jobs have now come back to help their families and continue the tradition of making mezcal.” With mezcal clearly working hard to establish its identity from the ground up, perhaps it’s finally the spirit’s turn to shine.

Mezcal’s new definitions

Under the new amendments, mezcal has to be made from 100 per cent agave (previously, up to 20 per cent of other carbohydrate spirits were allowed, for example sugarcane or corn). Common species used include espadin, cirial, arroqueno, mexicano, barril, cincoanero and salmania, with wild variety tobala. Next, there are now three categories of mezcal, depending on how they’re produced:

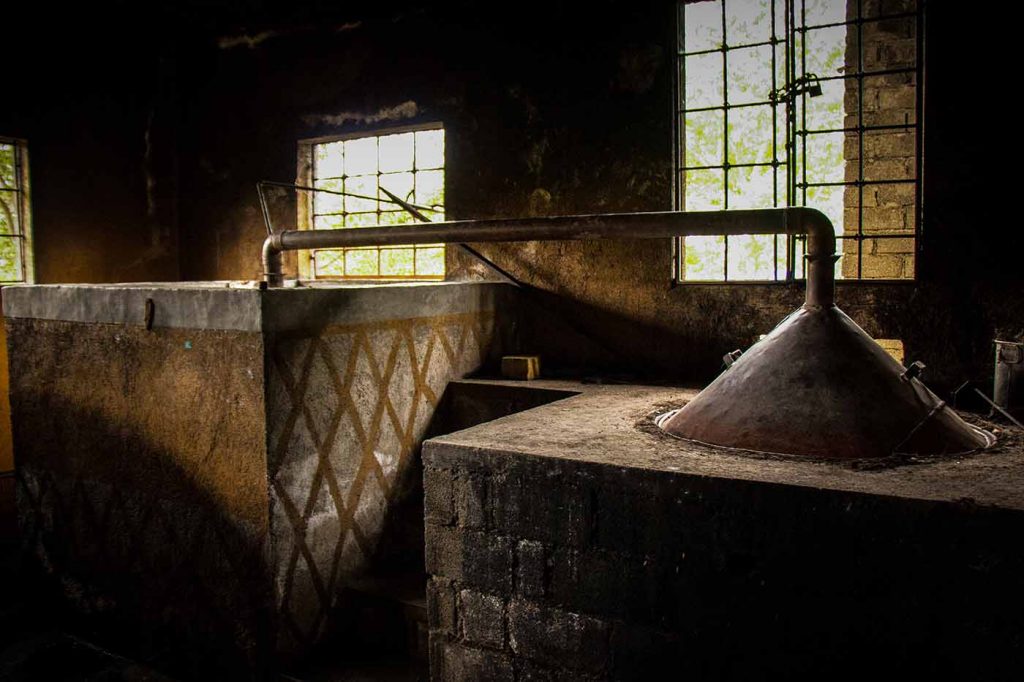

1 Mezcal. Refers mostly to industrially produced mezcals where the pinas are cooked in pit or above-ground ovens or autoclaves. The cooked agaves can be crushed with mechanical or hand-crushing mills; fermented in wood, stone or stainless steel; and distilled in pot stills or continuous columns of copper or stainless steel.

2 Artisanal mezcal. Covers producers who cook their harvested pinas in pit ovens or masonry wells, and mill them with modern shredders, but with emphasis on hand, stone or wooden milling. Fermentation has to take place in hollows of stone, soil or trunk, wood or clay containers or animal skins and can include maguey fibres. Distillation then takes place with direct fire under copper or earthenware stills, with wood, copper or clay still tops – the maguey fibres can remain in the wash.

3 Ancestral. The most rustic producers that fall into this category cook pinas in direct-fire pit ovens, and hand crush them in stone or wooden mills, before the agave sugars are fermented in animal hide, wood, earthen and stone vats with maguey fibres still unfiltered. To derive the mezcal, they have to put it through direct-fire clay stills with wooden or clay still tops, and the agave fibres may remain in the wash during distillation.

Finally, mezcals produced under those three sub-categories are further labelled with six finishes:

1 Blanco (white): unaged spirit.

2 Reposado (rested): stored in barrels for between 2 to 12 months. The new NOM-070 revision now allows Mexican woods to be used, as opposed to previous regulations that only allowed oak barrels to be used for ageing.

3 Anejo (aged): stored in barrels for 12 months and up.

4 Madurado (glass matured): this category bottles ancestral mezcal to mature in glass bottles.

5 Distilado con (distilled with): when a spirit is re-distilled with fruits, grains, or raw meats (most commonly chicken or turkey breast for pechuga styles) for additional flavour.

6 Abocado con (flavoured with): mezcals that are macerated or flavoured with flavour essences, or with an added worm after distillation.

This story was first published in Issue 04 of DRiNK Magazine.